Change is on the horizon, and I’m eagerly embracing it.

A few months back, I took a leap and became an independent disability support worker (as a side job after hours).

Despite lacking formal training in the disability sector, my personal experiences as a parent and sibling have equipped me with empathy, compassion, and the time to support others.

So, when I received my first booking four weeks ago, followed by another the next week, I eagerly accepted both roles.

My initial client was a young adult who relies on a wheelchair and needs transportation and support.

The second booking was with an adult in their thirties who lives alone and has both autism and multiple mental health diagnoses.

To my surprise, both clients rebooked me, and I’ve spent considerable time with the client in their thirties and only worked three shifts with the first client once their regular support worker returned from annual leave.

After each session, I take a moment to reflect and regroup in my car. I can’t help but notice how well-suited I am for this role and how much my unique services are appreciated.

However, a part of me wonders if I’m too soft-hearted for the job because I care too deeply (if such a thing is possible).

Through these experiences, I’ve come to recognise the profound isolation faced by adults with disabilities.

The importance of human connections and relationships has become more apparent as I spend time and engage in heartfelt conversations with my clients.

One asked if there was an NDIS-funded service that provided hugs, and shortly after, they asked if I could hug them.

Suppressing tears and feeling a tug at my heart, I responded professionally, explaining that it went against my professional boundaries to do so, but as a mother, I couldn’t resist saying yes.

The embrace lasted just a brief moment, but it felt like a lifetime. I let them take the lead in releasing the hug when they were ready, they thanked me and we parted ways.

By the time I reached my home, another booking request was waiting in my inbox for the following day but I declined knowing that it wouldn’t be healthy for them if they developed a dependency.

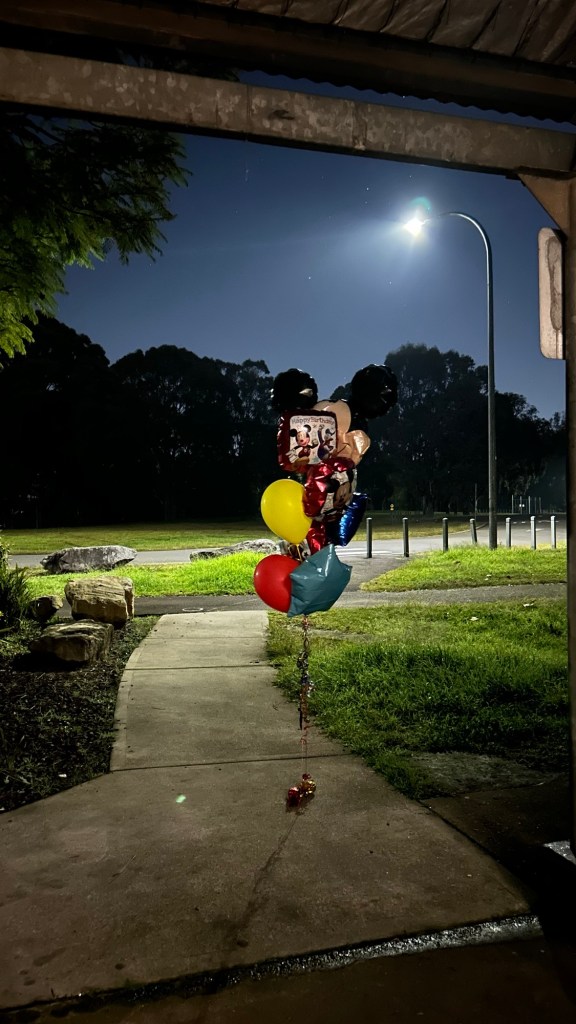

Since then, I’ve worked four shifts with this client, all scheduled late at night to accommodate their discomfort with being outdoors during the day.

We drive around, exploring different areas and parks and taking walks.

I provide them with privacy to freely release pent-up energy and aggression through stimming if needed.

We talk, or rather, they talk, and I listen.

Individuals who experience profound loneliness and isolation have so much to express and can speak for hours.

They share their feelings of having nobody, of being abandoned by everyone.

Their frustration with NDIS-funded services that overpromise and underdeliver is entirely justified.

They express gratitude for my unwavering presence and that I’m not afraid of them due to their challenging behaviours.

The actual words are ‘thank you for not being scared of me’.

When we’re out and about, I notice the way people look at them.

Their ‘ blind disability’ makes them appear “normal” to those who are unaware of or unfamiliar with disabilities, especially autism.

Their unique stimming behaviour, resembling a repetitive dance step, and distinct dress style make them stand out.

Unfortunately, I’ve overheard people muttering derogatory terms like “junkie” or “retard” and whilst I don’t bring attention to their words I shoot them looks to show them their hurtful words are not appreciated.

This client jokingly refers to me as their “bodyguard.” When we enter a store together, they feel protected from judgmental gazes that assume they’ll steal something.

In the park at night, they feel safe in my presence, knowing that if they were alone, the police might mistake them for a threat.

Sometimes, I’m introduced as their chauffeur or support worker and, affectionately, as Mama P. However, I cannot accept the latter.

Their mother has distanced herself, and their siblings have been absent for quite some time.

Their biological father hasn’t been a consistent figure since their childhood and their only “friends” are individuals with mental illness or struggling with drug addiction.

The pain of their mother’s absence and the profound grief they feel is evident.

As they share stories, their conversation often takes a turn when the hurt becomes too overwhelming and tears well up in their eyes.

They tell me, “I want my mum.”

It’s heart-wrenching.

Despite their struggles, they possess intelligence, wit, and a wealth of knowledge.

They hope to prove everyone wrong by succeeding in life, but often, they contradict themselves.

They find it challenging to trust, and living this way is incredibly difficult.

They explain that admitting themselves to a mental health facility doesn’t cater to their autistic needs and behaviours, although it does help with their mental illness and suicidal tendencies.

They express gratitude for my consistency and dedication, but I’ve made the conscious decision not to accept all their booking requests.

I can see where this professional “relationship” may lead, and I don’t want to leave them with a sense of abandonment when I travel overseas later this year.

It’s a difficult choice to make.

Through this new role, I’m learning and growing.

My own life experiences have been my best teacher, and I am grateful for these two individuals who have provided me the opportunity to walk alongside them during these times.

Will disability support work be part of my next chapter? I have no idea, but for now it feels right.

Leave a comment